On Main Street and in Salt Lake City’s hardest-hit neighborhoods, the Downtown Ambassadors are here to help

This article has been shared from Salt Lake City Weekly By Benjamin Wood @BjaminWood

A pair of ambassadors stop to talk with a man on 300 South.

It’s a sweltering, 100-degree afternoon as Becca Rieger heads out of the Downtown Ambassadors’ office—in the historic Newhouse Realty Building—and toward Washington Square. She’s hard to miss in her bright yellow uniform, pushing a rolling garbage can across State Street, and she makes a point to smile, wave and say hello to everyone she passes.

There are roughly 30 people and six dogs resting in the shade to the north of City Hall. Rieger makes her way toward and through them, picking up any stray trash she sees and stooping to check on a man lying facedown in the grass, who rolls over and assumes the polite stranger is telling him to move along.

“I’ll be on my way,” he says, disoriented and half-asleep.

“No, you’re good,” Rieger replies. She invites him to a resource fair the next day at Pioneer Park, then continues along the sidewalk.

Typically, ambassadors like Rieger make this walk alone, providing outreach to the unsheltered, picking up litter and answering whatever questions they might encounter from visitors—like how to use Trax, where to find parking, which restaurants offer a good lunch menu and what special events are happening around the city. But today she’s trailed by two supervisors—Landon Olsen and Kristina Olivas—a consequence of the City Weekly reporter who also asked to tag along.

Olsen steps in to clarify that it’s not necessarily the ambassadors’ role to remove people from public spaces—though they will help to clear out folks who are impeding business and private property. Rather, Olsen says, the ambassadors are there to provide information and support and, when necessary, to report larger issues to the appropriate city departments. They do make a point to wake people who are sleeping on the street, he says, to confirm the person is capable of waking.

“That’s just to check on them and make sure they’re alive and well,” Olsen says.

Rieger gestures to the fanny pack around her waist and explains that she’s carrying Narcan, the brand-name version of the anti-overdose medication Naloxone. She says she has only needed to administer the medication once, relating an experience from last year when she was walking near a large encampment on 500 West and asked to help a man who was overdosing.

“He was OK, thank God. He woke up right there, but it took a couple doses,” Rieger said. “It was really scary, adrenaline was high. But it was awesome that we were there and able to do something about it.”

Rieger’s story is indicative of the work the Downtown Ambassadors do, which meets a critical need in the city’s operational ecosystem but is difficult to fully define and apt to go unnoticed by day-to-day residents, office workers and guests. Program staff and city officials say the ambassadors are making a difference, boosting both safety and vibrancy—but those intangible benefits don’t always resonate with Salt Lakers who are weary of the city’s seemingly intractable challenges.

“I’ve seen them pick up some garbage,” said Pete Marshall, owner of Utah Book & Magazine. “I don’t know what the hell their job is supposed to be.”

Marshall has been on Main Street for nearly 40 years—the family store is more than 100 years old—and he said there’s more unsheltered individuals downtown than ever.

He’s spoken to the ambassadors, who tell businesses to call them when they need help, and he’s made his share of calls to the police. But he’s skeptical that conditions downtown are improving.

“A lot of businesses around here just got tired,” Marshall said. “You call and no one shows up.”

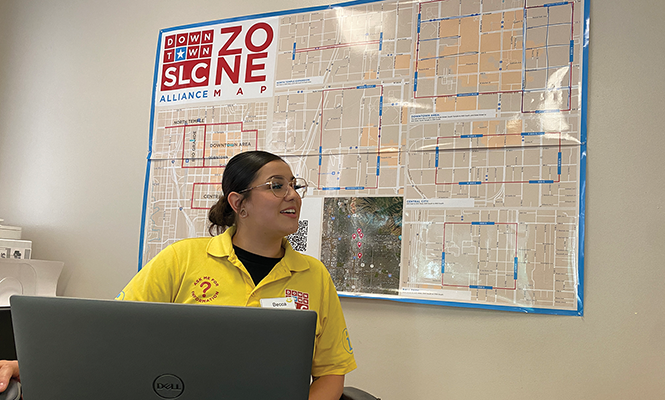

Becca Rieger prepares for a shift in front of a map of service areas. Photo by Benjamin Wood

Launched in 2017 by the Downtown Alliance, the Ambassadors program has since contracted with the city to expand into Central City and Ballpark—where homeless resource centers are located—and to the North Temple and Rio Grande areas. Michelle Hoon, program manager for the city’s Homeless Engagement and Response Team (HEART), said roughly $1.5 million from the city’s homelessness mitigation funds (state dollars awarded to cities that host resource centers) is used to support the program’s expansion, which she described as money well spent.

“They’re super beneficial,” Hoon said of the ambassadors. “They’re kind of like the first line of defense for problems that could come up.”

Hoon described the Downtown Ambassadors as “eyes and ears on the street.” And however one might perceive the state of the city—good or bad, declining or improving—Hoon said conditions would be worse without them.

“It keeps the problems manageable. It keeps the problems from really spinning out of control,” Hoon said. “They still do—there are places where you can get overwhelmed. But for the most part, we have got a pretty clean, pretty safe city. And I think a lot of that and the maintenance of these areas has a lot to do with the fact that we have the ambassadors there.”

It Takes a Village

Before the walk to Washington Square, Rieger and her fellow ambassadors met for their daily huddle. In a quick debriefing, Rieger noted the next day’s resource fair and a Family Fun Night happening that evening at Gallivan Plaza, and reminded the team to wear their uniforms correctly—including to “remove your yellows” during breaks from the summer heat—and to “stat” the bags of trash they collect.

After that, the group stood in a circle and was led through a warm-up routine of twists, leg raises and toe-touches by an ambassador named Solomon while a Fergie playlist ran in the background.

“Alright, let’s go do some good,” Solomon said, sending the ambassadors scattering like busy, yellow bees.

“Stay hydrated!” Kristina Olivas called out after them.

The ambassadors collect a lot of data, which is shared with the city’s HEART team on a weekly basis. Block by block, they’re directed to log everything from the number of people they encounter and the services offered to them to the amount of garbage they collect, which is then run up the ladder as both a quantitative and qualitative measure of the trends and hotspots taking shape in the city.

“If you can address an encampment when it’s small, you’re way more likely to be able to get that person or those couple of people into a service that’s going to support them,” Hoon said.

The ambassadors make regular use of the SLC Mobile app, while encouraging businesses and others to use it as well. The app functions as a clearinghouse for maintenance and enforcement requests, with users able to report everything from a malfunctioning sprinkler in a park strip to an illegally-parked car—each report already sorted to the appropriate jurisdictional entity.

“If there’s a broken streetlight, broken sign, graffiti, a pothole, you name it—we’ll put it on SLC Mobile,” Olivas said.

Ambassadors do a warm-up routine before walking the city. Photo by Benjamin Wood

The ambassadors only recently added trash collection to their roles, and both Hoon and Olivas credited that with boosting the program’s visibility and helping to build bridges with local business owners—it’s a visual indicator of the work they’re doing and their impact on the community. While the city has its routines for trash removal, it can be challenging for that work to address the detritus that accumulates not just day by day, but hour by hour as tens of thousands of people make their way through the city.

“The light trash pickup that they have been doing has been phenomenal,” Hoon said. “It’s worked wonders to help keep those neighborhoods more maintained.”

The program also relies on local businesses to dispose of that trash, as the ambassadors do not have their own dumpster. Olivas said that’s just one example of the partnerships they rely on to effectively do their work.

“We have had better communication, better connection and better buy-in to our service from the businesses than we’ve ever had before,” Olivas said. “You don’t need to communicate with us every single day. But if you ever need us, we’re here.”

As Rieger made her way up the sidewalk at Washington Square, several of the people resting there began gathering up their trash and approaching her to throw items away. Olsen noted that many of the areas where the unsheltered congregate don’t have garbage cans nearby and that it can be difficult to avoid littering when you’re carrying all of your possessions.

“The majority of people want to have a clean space,” he said. “I’m not sure the general population realizes that.”

Asked about trends in the city, Olivas noted the increased amount of resources for the unsheltered that came online over the winter, like the micro-shelter community on 600 West and other support programs.

Having those additional resources gave ambassadors more and better options to offer to the people they encountered on the street, she said, and that in turn has led to more people accepting those offers and taking advantage of the help that is available to them.

“Those shelter resources have continued to stay open through the summer, so it’s really assisted our team and the individuals who are unsheltered,” Olivas said. “We’ve seen the trend of people saying ‘yes’ to shelter and ‘yes’ to getting into that safe space continue, because those options are available.”

And with talk of a new entertainment district around the Delta Center and Salt Palace, and the Power District taking shape along North Temple, the footprint and needs of Salt Lake’s urban core are ever expanding. Both Olivas and Hoon said there have not been formal discussions about adding new ambassador teams to those areas, but both also acknowledged the program could be a benefit to those development efforts.

Looking for fun things to do downtown? Ask an ambassador.

“Especially as we grow and we continue to create these areas of entertainment, our services are going to be needed more and more,” Olivas said. “We’ve seen our team grow into neighboring areas and we would love to continue to be that good neighbor and provide that support wherever it is needed.”

Lone Rangers

There are currently 25 ambassadors, up from six when the program first launched. They hit the streets from 7 in the morning until 11 at night in the summertime and until 7 p.m. in the winter. While some areas—particularly those outside of downtown—will see a pair of ambassadors working together, most go out alone in order for the program to cover as much ground as possible.

“It is an individual job, they are out there by themselves,” Olivas said. “But there’s someone always close by where they can get that help.”

It’s atypical work that rewards a unique set of skills—comfort in both isolation and diverse social interactions and a high tolerance for the unpleasant, from weather extremes to the realities of urban living often ignored by polite society.

“We’re really transparent about the job from the very beginning. They are told exactly what to expect—the pretty stuff and not so pretty stuff,” Olivas said. “We work in all weather and that’s what the team is told from the very beginning. We’re out there with the purpose of helping everyone at any time of the day.”

Fern Aguirre, general manager of Gracie’s, said she’s called the ambassadors for help several times. With the bar’s patio and entrance facing out onto West Temple, she said there have been instances where a person on the street or sidewalk might be shouting profanities, asking for money or otherwise disturbing her customers.

“We find ourselves in situations like that where a police presence might not be necessary,” Aguirre said. “Especially if they’re out on the street, that’s not something where I feel comfortable sending my staff out there to handle.”

She said the ambassadors have been prompt to respond on the occasions she’s reached out for help, typically arriving within 10 minutes. And she added that while she regularly sees the ambassadors making their rounds, it’s been some time since she had to proactively reach out to them for assistance.

“It definitely seems like—as far as the high-traffic areas downtown—we have seen improvement over the years,” she said. “The big scope, what do you attribute it to? Can you really say that this is the cause and effect? But I know that they’ve been great for us.”

Several ambassadors have a personal history with homelessness and addiction, which Hoon said gives them a lived experience that sets them apart from other public officials.

Light trash pickup was recently added to the ambassadors’ services.

“I think that gives them a different perspective on the work that they’re doing,” she said. “They’re really able to approach it with a lot of empathy and understanding and to speak the language of those who are out on the streets.”

Residents and businesses may not always see a full picture of the work the ambassadors do, but Hoon said the feedback she’s received has been nearly unanimous in praising their efforts.

“I have never heard anything but positive things to say about the Ambassador program,” Hoon said. “I think it’s really awesome that they’re able to get out there and provide a friendly face both for people who are unsheltered and also people in the business community.”

Aguirre noted that she’d like to see the program—or something similar to it—extend beyond 11 p.m. on weekends, at least around downtown’s nightlife spots.

“With the bars it’s kind of hard, because that’s kind of when a lot of the problems start,” she said.

In the late hours, when the ambassadors are not available, businesses like Gracie’s turn to the police for help. And while Aguirre emphasized that she has a great working relationship with the city Police Department, she added that having cops stationed outside of a bar doesn’t make for the best customer experience—even if no one is doing anything wrong—and that law enforcement isn’t necessarily the best solution to what people on the street are experiencing.

“A lot of times, these people are already in a tough situation,” she said. “I know that having them arrested is not going to do me, the police officers, the city or anybody any favors.”

Unseen Effort

It takes about an hour for Rieger to complete a full lap of Washington Square, with much of the work concentrated around the northeast corner, where 400 South reaches the Main Library and 200 East. Rieger heads back toward the Newhouse Realty building, to dispose of both the container of trash she’s collected and the City Weekly reporter shadowing her.

While Rieger and Olsen punch in the code to a gated dumpster, Olivas notes how much was accomplished in a short amount of time, and how unlikely it is that a typical Salt Laker would notice.

“The impact that we have in that hour—we collected a whole bag of trash, we connected with more than 20 people, we informed them of the resources,” Olivas said. “It’s all of these things happening in that hour that no one really sees or understands unless they’re with us or we can show them through the data that we collect.”

Olsen comments on how face-to-face interactions have decreased in modern society, with fewer opportunities for chance encounters that nudge people out of their comfort zones. He says it’s one of the reasons he loves working for the Ambassador program, whether that interaction takes the form of offering aid to someone in need or simply helping an out-of-town visitor find their way through an unfamiliar city.

“The overall message is that we’re here to make this a vibrant community,” he says, “through cleanliness, through a friendly face, through connecting people to resources and being that walking knowledge base.”

Aguirre said the Downtown Ambassadors illustrate the bigger challenges at play in Salt Lake City—challenges like keeping the city clean, getting help to those who need it and finding the right spaces for those with nowhere else to go. The ambassadors may not be capable of solving all of those problems, but she said their presence adds to the quality of the city.

“Ultimately, we’ve found benefits from it,” she said. “All of the people who have come out, we’ve had good interactions with. They’ve helped us.”